Dynamo Moscow won the first Soviet Championship in 1946.

photo: Vladimir Nabokov Collection

This story is also available in Russian language. Статья на русском языке.

Ice hockey was established in Russia only with the second attempt. In 1911, representatives of Sport Club Sokilniki Moscow tried to join the International Ice Hockey Federation but they neither had the approval back home, nor did the sport actually exist in Russia. Bandy was played in tsarist Russia – a type of hockey played with a ball and 11 players aside on an ice sheet the size of a football field – and someone did not understand that “Canadian hockey”, as ice hockey was called in Russia in those days, was a different sport.

In the mid-thirties, a team of hockey players from the German workers' sports union Fichte came to Moscow, played three exhibition games and lost all three to a Moscow team made up of bandy players. But the game with the puck did not leave any lasting impressions yet.

The Red Army in 1943 was still fighting on the territory of the Soviet Union, but the country's leadership was thinking about post-war life. Of course, in the first place were topics such as the restoration of industry, the revival of agriculture, but spiritual and physical culture was an equally important area. Physical culture and sports have proved their necessity for the life of the country in the most difficult moments of the war. Particular attention was paid to the program of the Olympic Games. And there was ice hockey.

Ice hockey was established in Russia only with the second attempt. In 1911, representatives of Sport Club Sokilniki Moscow tried to join the International Ice Hockey Federation but they neither had the approval back home, nor did the sport actually exist in Russia. Bandy was played in tsarist Russia – a type of hockey played with a ball and 11 players aside on an ice sheet the size of a football field – and someone did not understand that “Canadian hockey”, as ice hockey was called in Russia in those days, was a different sport.

In the mid-thirties, a team of hockey players from the German workers' sports union Fichte came to Moscow, played three exhibition games and lost all three to a Moscow team made up of bandy players. But the game with the puck did not leave any lasting impressions yet.

The Red Army in 1943 was still fighting on the territory of the Soviet Union, but the country's leadership was thinking about post-war life. Of course, in the first place were topics such as the restoration of industry, the revival of agriculture, but spiritual and physical culture was an equally important area. Physical culture and sports have proved their necessity for the life of the country in the most difficult moments of the war. Particular attention was paid to the program of the Olympic Games. And there was ice hockey.

Video: Russian State Archive of Film and Photo Documents

With a trip to England in 1945, the players of Dynamo Moscow learned more about ice hockey. The players – among those invited was a soldier named Vsevolod Bobrov – went to the Crystal Palace skating rink in London. It was played there mainly by Canadians who were based in England during the war. Then the Russian players, and almost all were football players who started to skate in the winter, found out what ice hockey looked like.

The "father" of hockey in the USSR was Sergei Savin, who worked in the football section of the country’s Sports Committee. To begin with, he was advised to go to the Baltic republics Latvia and Lithuania since they practised this style of hockey even before the war. The Latvian national team even participated in the 1936 Olympic Games and both Latvia and Lithuania in IIHF Ice Hockey World Championships. He collected information, a circular letter was sent to sports societies and organizational activities began to launch the sport in the Soviet Union.

To begin with, they decided to hold a meeting in Moscow on the rules of the game; they had to be explained to the coaches and future referees. The Rule Book they possessed was in German, and the reading of the rules took place in the club hall under the stands of the Dynamo stadium. The main figure was Edgars Klavs from Riga – a football and ice hockey referee who spoke Russian. His assistant translated the rules from German to Latvian, and Klavs to Russian. The learning process went quite smoothly until they stumbled upon what we know as a penalty shot.

In German, it was Strafschuss, which means, well, penalty shot. But the time was post-war and they did not want to use the word “shot”. And Klavs began to discuss with his assistant in Latvian how this same penalty shot is executed and the word “bullis” – a bull-calf – was heard several times. They wanted to immediately clarify that the player moves out of the centre circle, swaying like a young bull. But then Arkadi Chernyshev showed his impatience: "What is there to discuss, we write down ‘bullit’!" And this new word in the Russian language has been holding on for 75 years.

The hockey players did not refuse anyone’s help. The Dynamo team was helped by a captured German who worked at a construction site in Moscow, the army team was taught to play with the puck by an athlete, USSR triple jump champion Boris Zimbriborts, who played hockey in Harbin, China, before the start of World War II, and at Spartak the best player was Zdenek Zikmund, a Russian-born tennis player of Czech origin.

Armed with the rules, the players dispersed to cities and villages to begin preparations for the first national championship. This championship was attended by 12 teams, divided into three groups.

The "father" of hockey in the USSR was Sergei Savin, who worked in the football section of the country’s Sports Committee. To begin with, he was advised to go to the Baltic republics Latvia and Lithuania since they practised this style of hockey even before the war. The Latvian national team even participated in the 1936 Olympic Games and both Latvia and Lithuania in IIHF Ice Hockey World Championships. He collected information, a circular letter was sent to sports societies and organizational activities began to launch the sport in the Soviet Union.

To begin with, they decided to hold a meeting in Moscow on the rules of the game; they had to be explained to the coaches and future referees. The Rule Book they possessed was in German, and the reading of the rules took place in the club hall under the stands of the Dynamo stadium. The main figure was Edgars Klavs from Riga – a football and ice hockey referee who spoke Russian. His assistant translated the rules from German to Latvian, and Klavs to Russian. The learning process went quite smoothly until they stumbled upon what we know as a penalty shot.

In German, it was Strafschuss, which means, well, penalty shot. But the time was post-war and they did not want to use the word “shot”. And Klavs began to discuss with his assistant in Latvian how this same penalty shot is executed and the word “bullis” – a bull-calf – was heard several times. They wanted to immediately clarify that the player moves out of the centre circle, swaying like a young bull. But then Arkadi Chernyshev showed his impatience: "What is there to discuss, we write down ‘bullit’!" And this new word in the Russian language has been holding on for 75 years.

The hockey players did not refuse anyone’s help. The Dynamo team was helped by a captured German who worked at a construction site in Moscow, the army team was taught to play with the puck by an athlete, USSR triple jump champion Boris Zimbriborts, who played hockey in Harbin, China, before the start of World War II, and at Spartak the best player was Zdenek Zikmund, a Russian-born tennis player of Czech origin.

Armed with the rules, the players dispersed to cities and villages to begin preparations for the first national championship. This championship was attended by 12 teams, divided into three groups.

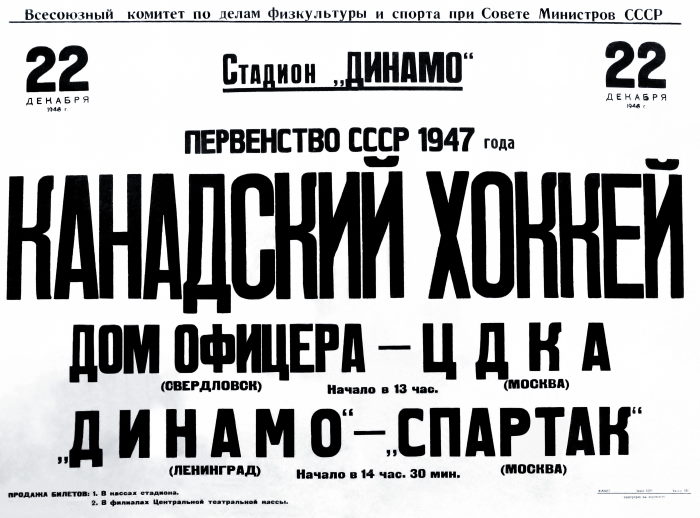

Poster for the opening day of the first Soviet Championship in what was then called "Canadian hockey" in Russia.

The following clubs were the pioneers: CDKA Moscow, VVS MVO Moscow, Dom Ofitserov Sverdlovsk, Dom Ofitserov Leningrad; Spartak Moscow, Dinamo Riga, Dynamo Tallinn, Dynamo Leningrad; Dynamo Moscow, Vodnik Arkhangelsk, Kaunas, Spartak Uzhgorod. All teams were from the Russian part of the Soviet Union except the teams from Kaunas, Riga and Tallinn from the Baltic republics.

The very first goal in Russian hockey history was scored on 22 December 1946 on the ice in Arkhangelsk by Arkadi Chernyshev, who was at that moment the playing-coach of Dynamo Moscow.

The championship ended on 26 January 1947 and the first champion of the country was Dynamo Moscow. Three teams from Moscow – Dynamo, CDKA and Spartak – scored the same number of points, and the winner was determined by the best goal difference. The first stars also appeared on the scene: Arkadi Chernyshev for Dynamo, Vsevolod Bobrov for CDKA, Zdenek Zikmund with Spartak, and at VVS Anatoli Tarasov. The best scorer was Tarasov with 14 goals – assists were not recorded.

The very first goal in Russian hockey history was scored on 22 December 1946 on the ice in Arkhangelsk by Arkadi Chernyshev, who was at that moment the playing-coach of Dynamo Moscow.

The championship ended on 26 January 1947 and the first champion of the country was Dynamo Moscow. Three teams from Moscow – Dynamo, CDKA and Spartak – scored the same number of points, and the winner was determined by the best goal difference. The first stars also appeared on the scene: Arkadi Chernyshev for Dynamo, Vsevolod Bobrov for CDKA, Zdenek Zikmund with Spartak, and at VVS Anatoli Tarasov. The best scorer was Tarasov with 14 goals – assists were not recorded.

Anatoli Tarasov took care of the flag.

photo: Vladimir Nabokov Collection

And although the tournament was short with 30 games and 191 goals, there were many funny situations. But most important the fans liked the game. It did not only carry excitement but also opened up new opportunities. Of course, ice hockey had its opponents as well with the tradition of bandy but sound policy prevailed.

In the winter of 1947/1948 the sports leadership of the USSR decided to send observers to the Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Sergei Savin went there by train via Prague. He met with the leaders of Czechoslovak ice hockey and agreed that after the Olympics a team of hockey players will come to Moscow for exhibition games. In St. Moritz he became convinced that he was right in his decision to invite future the Olympic silver medallists.

In 1948, the LTC Prague team flew to Moscow, which in fact was the backbone of the Czechoslovak national team. The guests won one game, the hosts the second and the third ended in a tie. The hosts welcomed the Czechoslovak team with Russian hospitality. And when the hockey players were at a banquet, several people entered their dressing room, copied and photographed protective equipment, which was not produced in the USSR at that time. Among the first researchers of the equipment was Spartak forward Anatoli Seglin, who later became an international referee and worked at World Championships.

In the winter of 1947/1948 the sports leadership of the USSR decided to send observers to the Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Sergei Savin went there by train via Prague. He met with the leaders of Czechoslovak ice hockey and agreed that after the Olympics a team of hockey players will come to Moscow for exhibition games. In St. Moritz he became convinced that he was right in his decision to invite future the Olympic silver medallists.

In 1948, the LTC Prague team flew to Moscow, which in fact was the backbone of the Czechoslovak national team. The guests won one game, the hosts the second and the third ended in a tie. The hosts welcomed the Czechoslovak team with Russian hospitality. And when the hockey players were at a banquet, several people entered their dressing room, copied and photographed protective equipment, which was not produced in the USSR at that time. Among the first researchers of the equipment was Spartak forward Anatoli Seglin, who later became an international referee and worked at World Championships.

LTC Prague in Moscow in 1948.

photo: Vladimir Nabokov Collection

After this series of games, the sports executives began to consider participating in the World Championships. But first, it was necessary to solve a lot of technical issues. The USSR entered the Olympic movement and in 1952 already participated in the Summer Games in Helsinki. A few months before during the 1952 Olympic Winter Games in Oslo they met with the IIHF leadership and applied for membership, which was approved a few weeks later. The USSR national team could participate in the 1953 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship in Zurich and Basel, Switzerland. But there was no confidence in success and the country didn’t want to lose especially as star player Bobrov was injured. Instead the team went to the Universiade in Vienna, where they won the championship with ease.

In autumn 1953 when preparations for the new season began and the 1954 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship in Stockholm, Sweden was already ahead, there was a rebellion in the team as the team leaders refused to play under Tarasov’s leadership. A special commission dealt with this situation and came to the conclusion that it was worth replacing the head coach. Arkadi Chernyshev was invited in Tarasov’s place. The team gelled together and the exhibition games in Finland showed that one could count on a positive result.

The USSR national team sensationally won in its first World Championship participation in 1954 including a 7-2 win against a confident Canadian team. It was the beginning of a great rivalry.

The Canadians got their revenge the following year, beating the USSR national team in Germany 5-0. This game added fuel to the fire. The next critical meeting was the 1956 Olympic Winter Games in Italy where Canada was represented by the Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen. That game turned out to be even but after a break for ice cleaning in the second period demanded by the Canadians, it was the Soviets, who scored for a 2-0 win.

The Canadians went to their rivals when the horn sounded. “We were afraid that they would fight out of frustration,” Viktor Shuvalov recalled. But the Canadians, like real gentlemen, were the first to congratulate the new Olympic champions.

This was just the beginning of the long story of Russian hockey 75 years on this day after the first puck drop of the first Soviet championship.

In autumn 1953 when preparations for the new season began and the 1954 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship in Stockholm, Sweden was already ahead, there was a rebellion in the team as the team leaders refused to play under Tarasov’s leadership. A special commission dealt with this situation and came to the conclusion that it was worth replacing the head coach. Arkadi Chernyshev was invited in Tarasov’s place. The team gelled together and the exhibition games in Finland showed that one could count on a positive result.

The USSR national team sensationally won in its first World Championship participation in 1954 including a 7-2 win against a confident Canadian team. It was the beginning of a great rivalry.

The Canadians got their revenge the following year, beating the USSR national team in Germany 5-0. This game added fuel to the fire. The next critical meeting was the 1956 Olympic Winter Games in Italy where Canada was represented by the Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen. That game turned out to be even but after a break for ice cleaning in the second period demanded by the Canadians, it was the Soviets, who scored for a 2-0 win.

The Canadians went to their rivals when the horn sounded. “We were afraid that they would fight out of frustration,” Viktor Shuvalov recalled. But the Canadians, like real gentlemen, were the first to congratulate the new Olympic champions.

This was just the beginning of the long story of Russian hockey 75 years on this day after the first puck drop of the first Soviet championship.